Prompted by my first experience of unprepared loss, I began pondering my personal relationship with death and how I could help my family and myself prepare in advance for when the time would come. In this article, I ask the question: how can I design a game that facilitates a more empowering end-of-life planning experience?

What’s really amazing about games is how they change our emotional response to challenges.

Jane McGonical

GAME THINKING MEETS DEATHCARE

The idea of combining serious subjects with game mechanics is not a new one. In fact, that’s how “serious games” got its name. One of the most serious subjects of them all, death and dying, has also become a topic of increasing interest amongst fields of design, healthcare, and academia. Researchers recently discovered that our brains naturally protect us from the notion of existential threat, a self-protecting mechanism most commonly known as ‘death-denial’*. The result of this death-denial phenomenon, both on a personal and societal level, is that we are rarely confronted with the need to prepare for death until it is too late. Being unprepared for dying can leave lasting scars on all involved, but it doesn’t have to be that way.

A few applied games developed in the recent decades have offered their solutions by making end-of-life conversations more accessible. “The Death Deck”, “The Hello Game”, and “Go Wish” are all examples of applied games that support people to various degrees in reflecting and talking about death and dying in a social way. Game as a medium can help lower the emotional threshold usually required to engage with the subject as well as offer a more structured approach in navigating through its complexities. I believe there is room for much more tools, creativity, and interdisciplinary initiatives to address this social challenge.

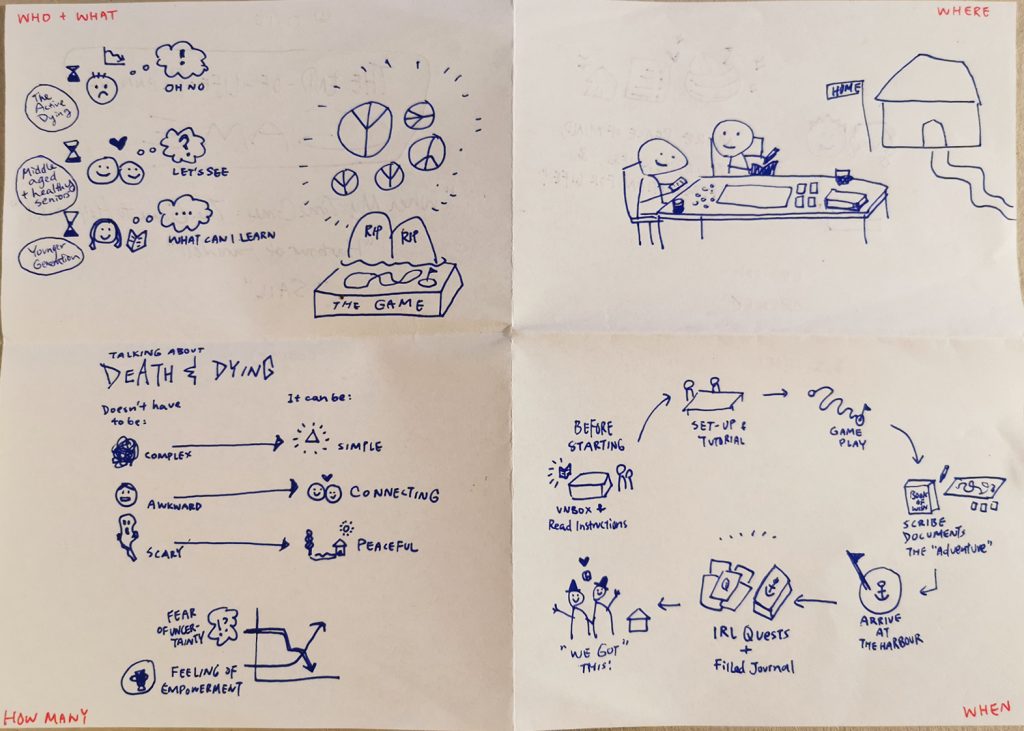

In this article, I present my research findings in the beginning design phase of a game that takes a collaborative approach in facilitating end-of-life planning conversations with family and loved ones. Based on the psychology that ‘it is much easier to help another person than it is to help ourselves’ the game facilitates players to both give and receive support in reflecting on various aspects of end-of-life planning. The social recognition and feedback loop thereby create a positive spiral that instills confidence in players’ own capacity to navigate the topic.

ABOUT THE GAME

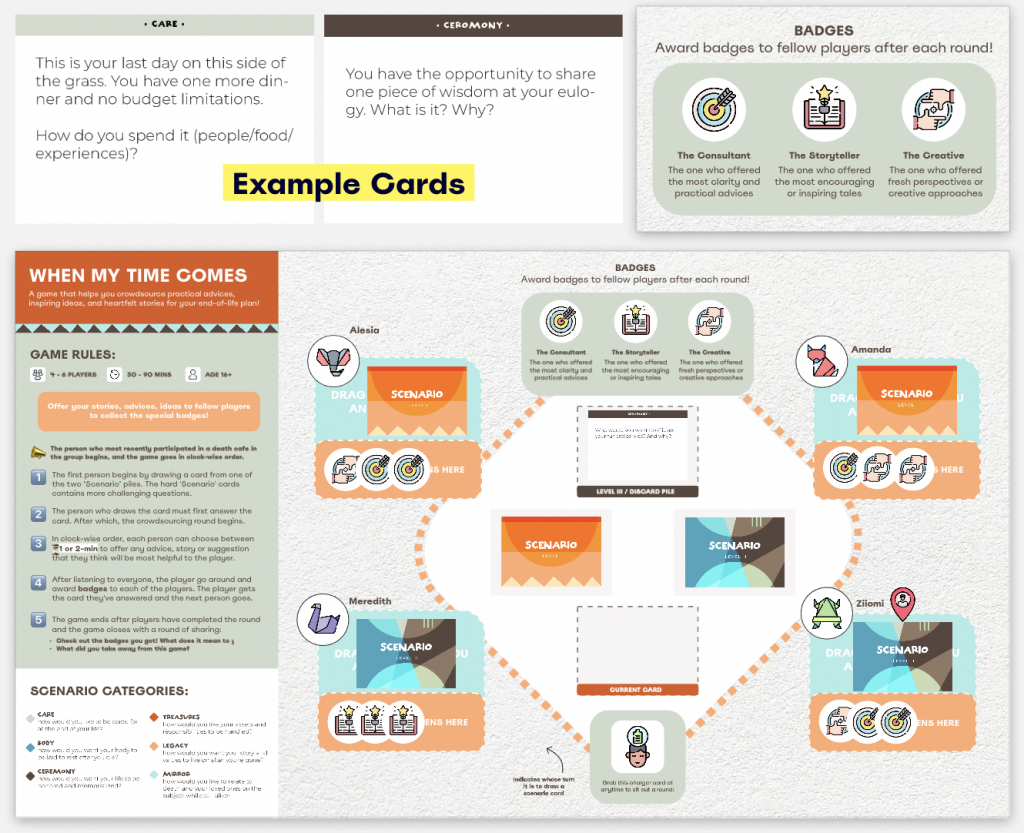

“When My Time Comes” is a conversation game where players get to offer as well as crowdsource practical advice, inspiring ideas, and personal stories for their end-of-life planning.

Inspired by the format of a death-cafe where people get together to talk about death in a cozy setting, the game is designed as a tool that can support death care professionals in offering more compassionate structures for end-of-life conversations.

In each turn, a player answers the scenario card they pick before a round of “receiving” begins where each player offers a response with the intent of providing support and value to the first player. Each turn then ends with the first player awarding the badge they deem fit to each of the players.

THE DESIGN PROCESS

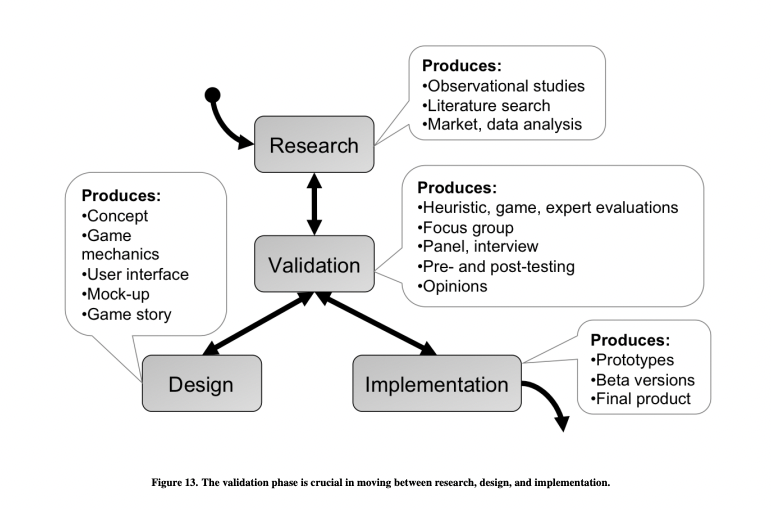

The design process for the game began with research. Observational studies are background work conducted before formulating the game concept during the research phase. Because end-of-life planning games are very specialized, it was difficult to find people playing such a game to observe. Instead, this was replaced by thoroughly researching the subject area and personally test playing the available end-of-life conversation games. Specifically, the GoWish game and the Death Deck.

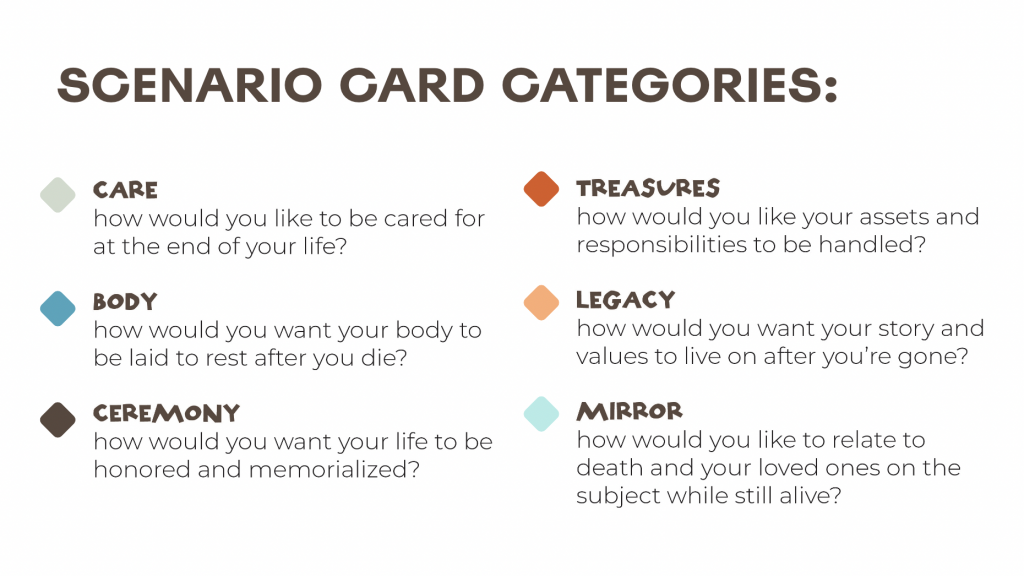

To gain insights into what the subject of end-of-life planning involves, I took an online course called “End-of-life Planning Made Simple” taught by death doula, Alua Arthur. Like the title suggests, the course provided a simple, comprehensive, and accessible way to navigate the seemingly burdensome task of end-of-life planning. After taking the course, I extracted themes from the course which formed the 6 categories within the “Scenario” cards.

There were significant limitations in conducting field research due to COVID-19, however, I was able to visit the Dutch funeral museum “Tot Zover” which showcased cultural death traditions from around the world and the latest innovations of deathcare.

During the lockdown, my field research focused instead on participating in online events, which included attending an end-of-life online exhibition and death cafe.

Using myself as the extension of my target group, I began defining the audience for the game – a relatively young generation who are seeking out death-related resources to better prepare for their own end-of-life and to support their loved ones.

PRE-TESTING

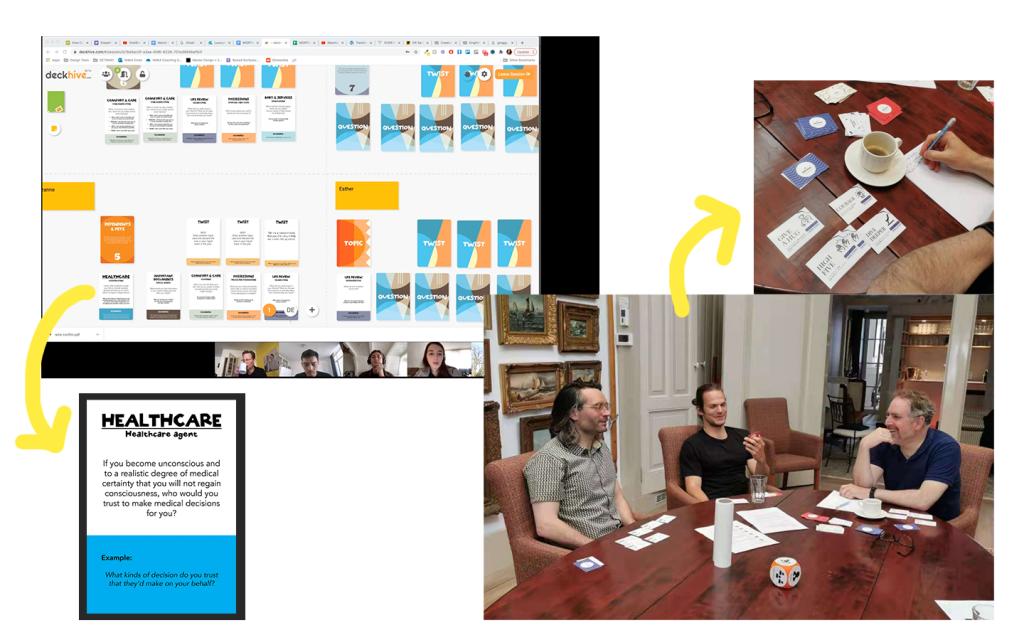

After developing the concepts further, I made 2 concept prototypes which I test played with classmates (online) and friends (offline).

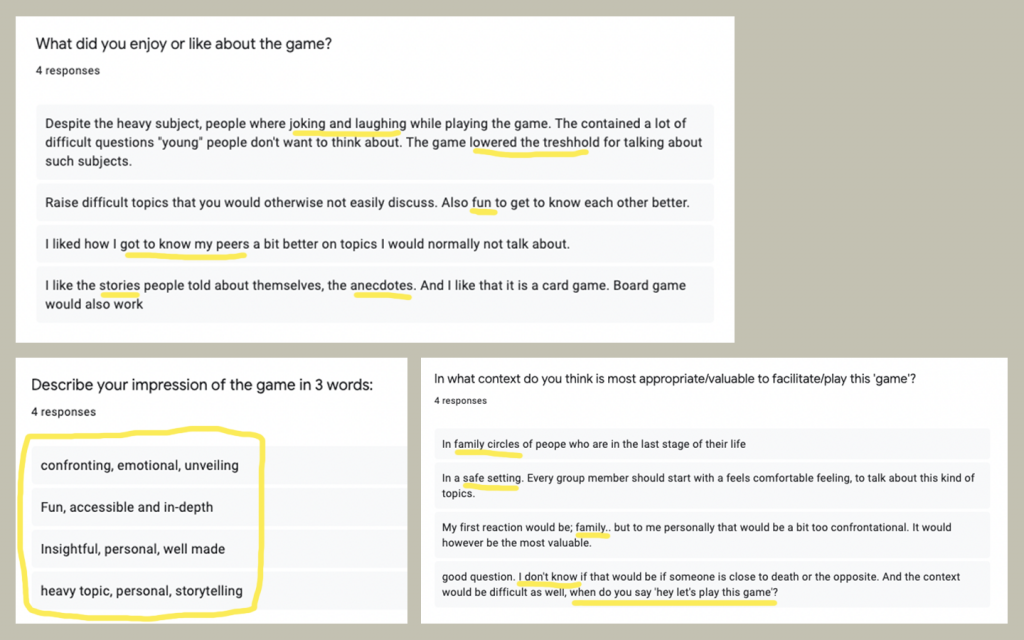

Although the classmates shared many positive impression on the game, they found it hard to pin-point the exact context in which the game would be played – “When do you say ‘hey let’s play this game’?” At this point, I realized that feedback and insights from domain professionals was necessary for further clarity.

I then reached out to Alua Aurthur and her organization Going with Grace and was met with a warm response from the program director Tracey. She shared that there has been steady growing interest in their online programs, especially in their certification training for death doulas. The profile of their students are all-ages and diverse in professional backgrounds with roughly 40% working within healthcare – a close match to the game’s target audience. So far, they have trained over 1,000 students from 17 countries around the world to become death doulas, and about 100 more students are added to that every quarter. Tracey offered to connect me with the wider network of past graduates and student guides to help me source volunteers, play-testers, and domain experts.

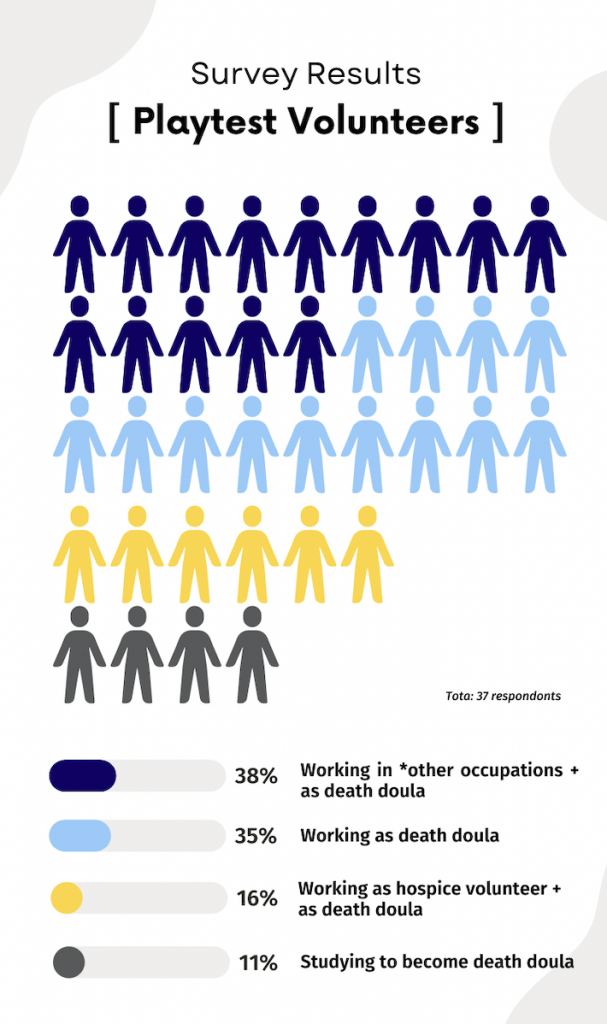

Shortly after our initial meeting, Tracey posted an open call for me in their network seeking volunteers for the first rounds of play-tests. I closed the submission within a few days after receiving more than enough sign-ups.

Among the 37 sign-ups, I discovered that the majority of the group worked more than just as a death doula, some of them working in overlapping fields as a “death cleaner”, “medical social worker”, “family physician”, and “anthropologist working on end of life issues” and others; such as “tattoo artist”, “urban planner”, “professional dancer”, and “flight attendant”. It seems that the profession of being a death doula is still an emerging field with many market opportunities in deathcare.

PLAY-TEST SESSION

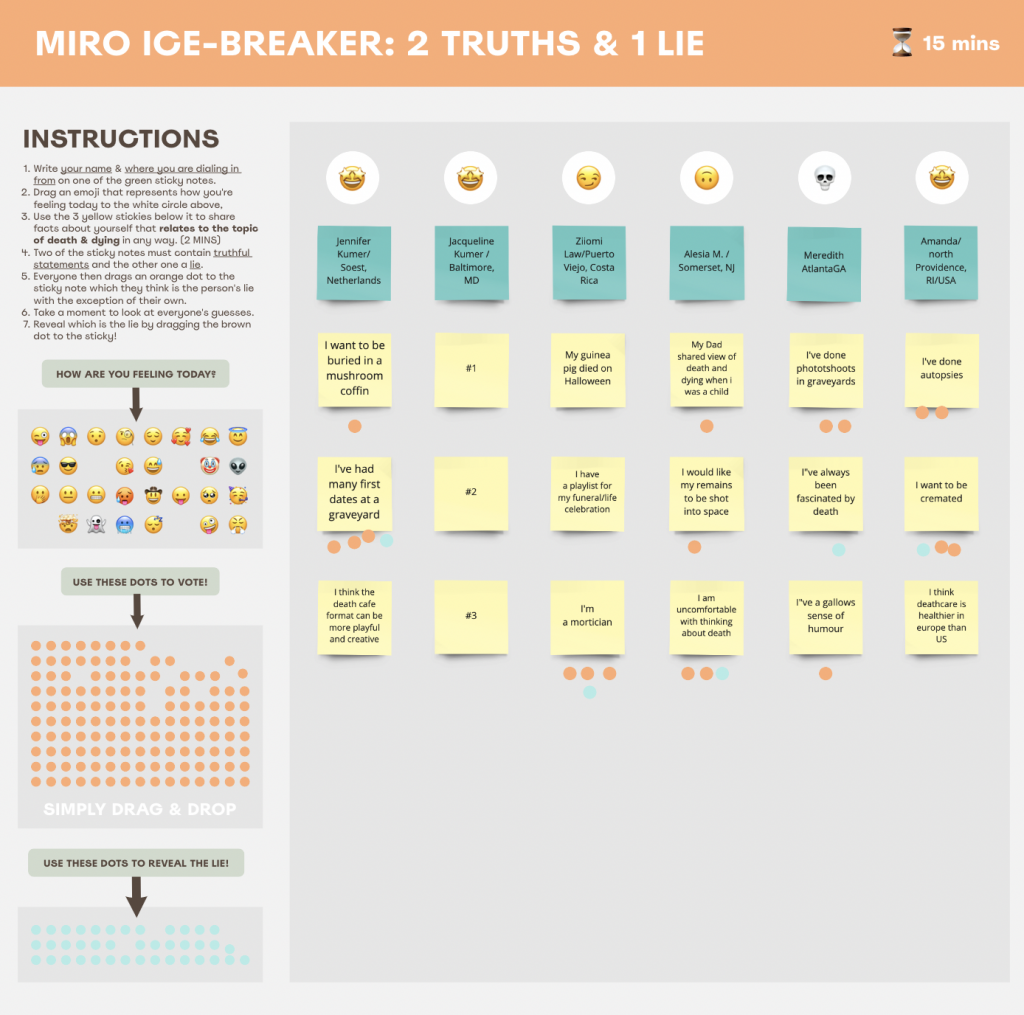

Two playtest sessions were hosted over Zoom with one assistant and 4 play-testers for each game. Each play-test session was conducted as follows; The 90-minute playtest was hosted via Miro in three parts on three boards. The first board hosts the ice-breaker (20 minutes), the second board the official play-test (50 minutes), and the third board the post-playtest feedback (20 minutes).

In the ice-breaker game, 2 truths & 1 lie, participants type in the sticky notes 3 facts about themselves that relate to the theme of death and dying. And by way of dot-voting, participants vote on what they think is the lie and get to know one another. The ice breaker serves the additional purpose of familiarizing participants to using Miro.

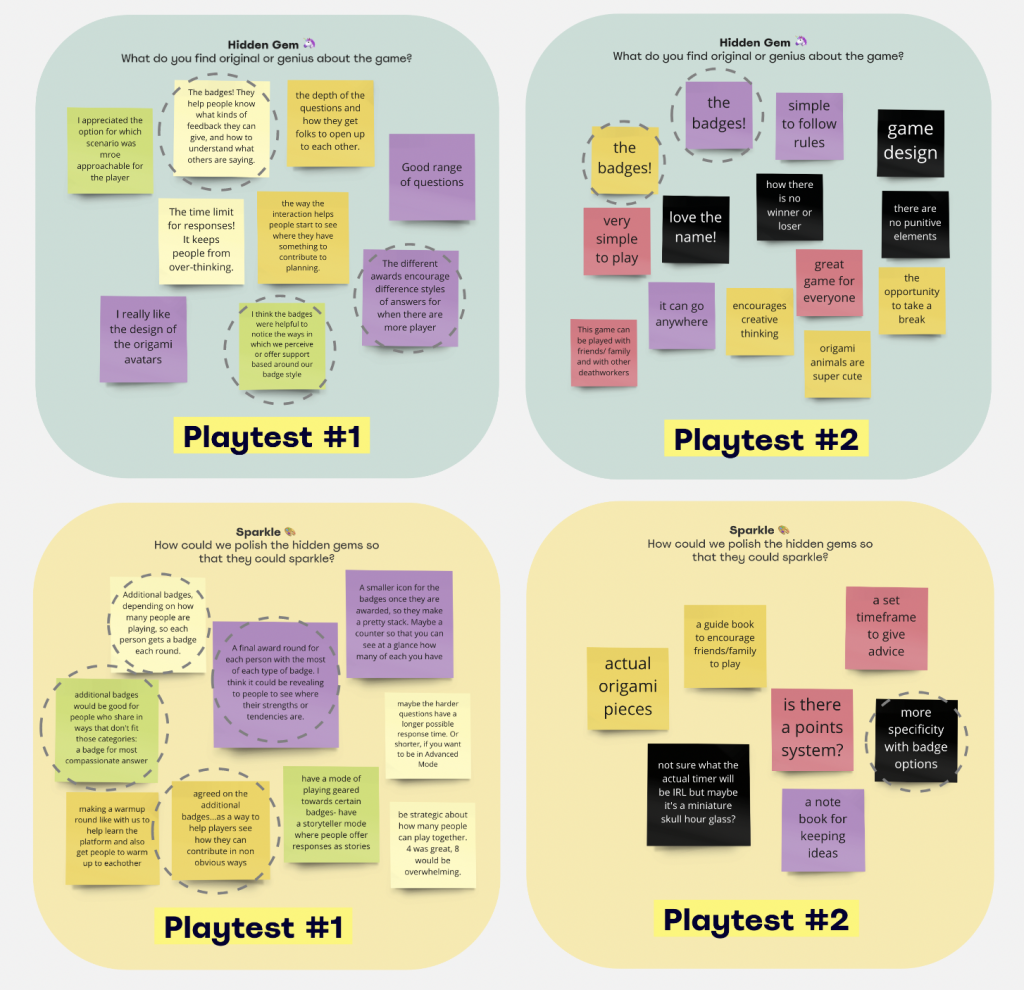

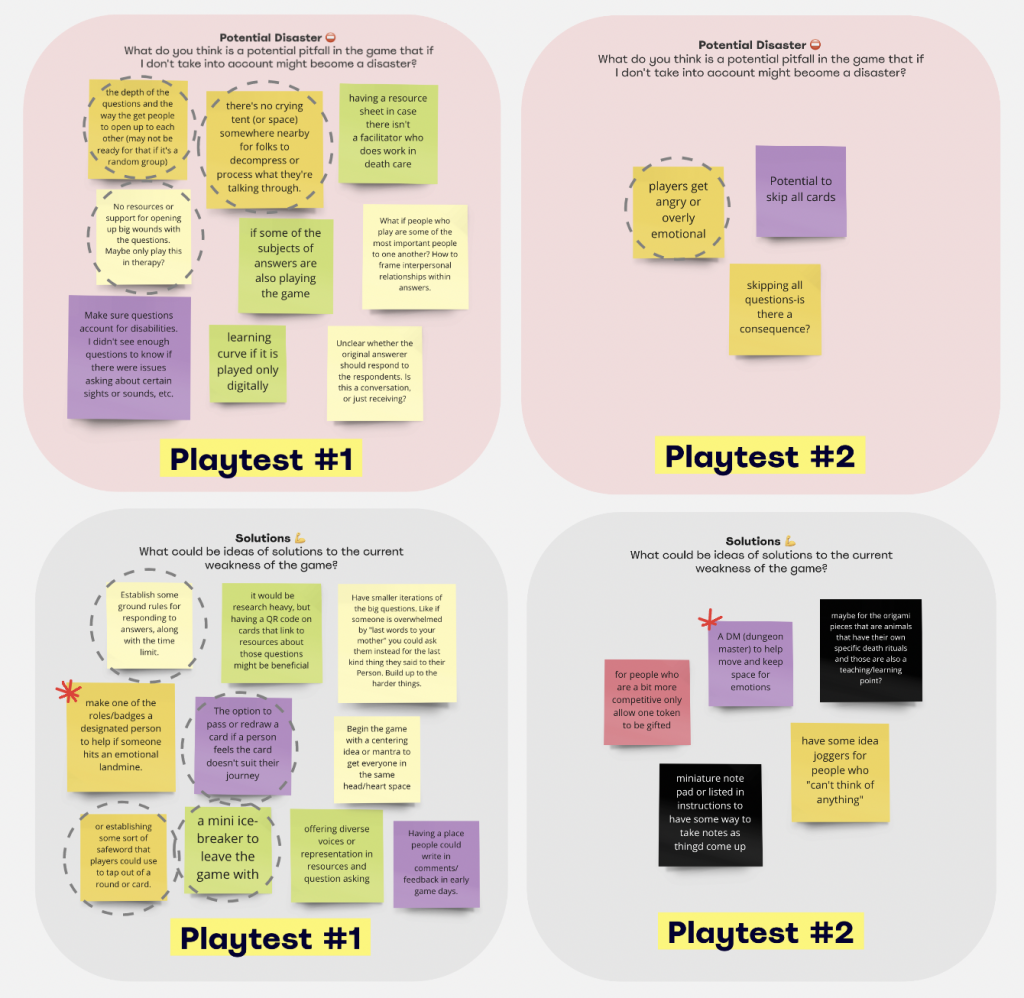

In the post-playtest feedback, participants were asked to generate as many sticky notes as they can in a limited time frame as responses to the 4 questions asked.

Potential Disaster: What do you think is a potential pitfall in the game that if I don’t take into account might become a disaster?

Sparkle: How could we polish the hidden gems so that they could sparkle?

Solutions:What could be ideas of solutions to the current weakness of the game?

POST-PLAYTEST FEEDBACK

A 2-minute timer is set for each of the four questions and participants are asked to generate as many sticky notes with their responses as possible. After the four rounds of written feedback, we enter a 20-minute open discussion where I ask participants to elaborate further on specific sticky notes.

As 1) Hidden Gems and 3) Sparkle, 2) Potential Disaster and 4) Solutions are directly linked to one another, they’ll be examined and evaluated together.

Hidden Gems & Sparkle

Many players complimented how the badge system helped players frame their responses towards one another, which shows how different perspectives can be supporting for others. In the words of Katie, the game offers a “compassionate structure” that facilitates a positive communal experience.

They also suggested the addition of more badges. However, Bruno, from his expert opinion, advised that having too many badges can potentially lead to unnecessary complexity; which can have a negative impact on the flow of the game. He advised that between 3-5 badges is usually the right amount. To confirm this, I’ll add two more badges to the game and assess in future play-tests.

Potential Disasters & Solutions

At the end of the open discussion, the group brainstormed together which led to 3 major iterations to the game.

#2 An empty slot for level 3 cards: players can discard any level 1 or 2 scenario cards that they do not wish to answer. The discarded pile, faced upwards, become a pile that other players can pick from in the next rounds

#3 A closing circle at the end of the game: each player takes turns to share their response to the following question to bring closure to the game.

After implementing these iterations to the game in the 2nd play-test, comments on potential disasters decreased significantly. A feedback that has yet to be considered that would potentially lead to new iterations is how the game dynamic might be challenged if players were close family members rather than strangers or friends. This scenario will be assessed and explored in future play-tests.

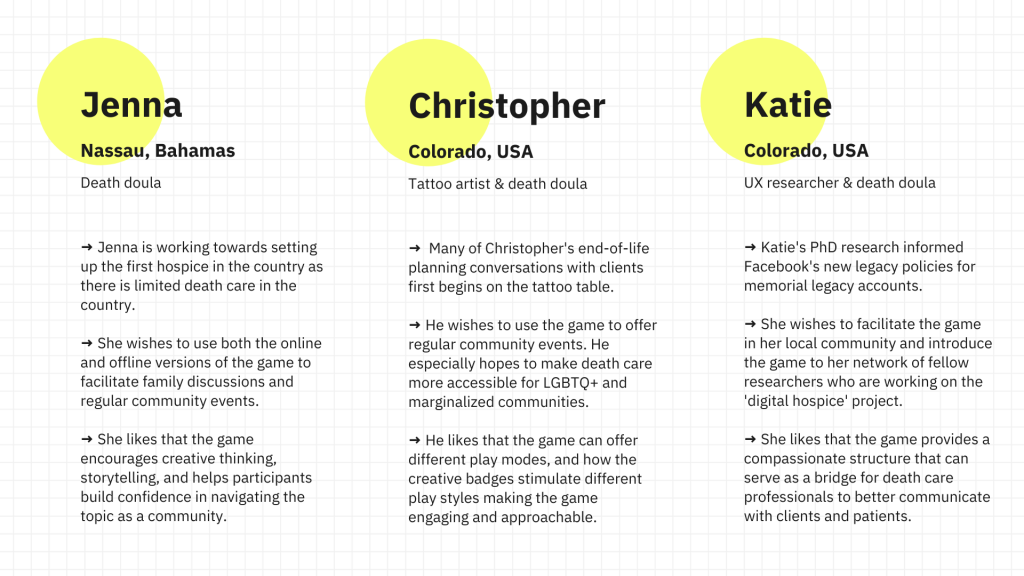

The overall positive feedback from the 2nd play-test indicated to me that the game was ready for a round of blind-play testing where the death care professionals would play the game within their context. To prepare for this next phase, I interviewed 3 play-testers/death doulas who volunteered to host the game with their participant groups – Jenna, Christopher, and Katie.

INTERVIEW

A summary of player’s feedback on what they found most valuable about the game was:

1. A structured approach that simplifies end-of-life planning into relatable “scenario” categories

2. Game mechanics that encourages creative thinking, empathy, authentic relating, and a rewarding experience that helps participants make progress towards their end-of-life plan

3. The game offers a communal experience that invites people to engage with the subject through different perspectives with one another in an open and compassionate way

NEXT STEPS

With multiple blind play-tests scheduled in the near future, the next steps of the project will focus primarily on how the game can be implemented in the context of death care to support professionals and their communities. This will include further game development and iterations based on evaluated feedback from play-testers and possible critiques from subject matter experts.

A physical prototype of the game will also be produced and play-tested alongside the current online version hosted via Miro. Depending on future developments, the game could potentially migrate to other more suitable online platforms for better practicalities and user experience. Lastly, I’ll also be exploring large-scale production possibilities through partnerships, publishing, or alternative means.

Ultimately, I hope to offer the game as a secular and innovative solution to support communities and families in having better end-of-life conversations and by extension, contribute to shifting the collective mindset towards a more positive relationship with death.

LEXICON

GAME THINKING

Game thinking, as defined by Bruno Setola, refers to an approach in examining existing rules for interaction in typical non-game contexts from the perspective of a game designer. Instead of game-production as an outcome, it focuses on analyzing, understanding, and rethinking the ‘player motivations’ and ‘game mechanics’ that are at play beneath any given social dynamic. Being a game thinker is also synonymous with being a social designer that uses a game design lens when exploring how interactions can be more fair and engaging and thereby affecting social change.

APPLIED GAME

An applied game or serious game is a game designed for a primary purpose other than pure entertainment. They are typically designed to educate, inspire and change behaviors whilst also being fun to play. For that reason, applied games are often a popular strategy used by large industry sectors like education, health care, city planning, engineering, and politics. They are usually developed in collaboration between an applied game developer and company leaders or experts to address a certain topic.

BLIND PLAYTEST

Blind playtesting is the last stage of playtesting when the game is given to other people with no instructions on how to play. If the game designer is present, they can only be strictly an observer without being able to assist or answer the player’s questions. Blind playtests are useful usability tests for the rules and game dynamics.

DEATHCARE

The death care industry is a highly decentralized and interdisciplinary one as it includes any professionals whose work involves caring for the dead, dying, and bereaved. Although the first point of care is often clinical, involving healthcare professionals such as doctors, nurses, and end-of-life workers, it can take on a variety of courses depending on cultural, religious, and personal preferences, involving a range of people from religious figures, undertakers, to grave keepers among others – all of these roles formulates what can be known as deathcare workers.

DEATH DOULA

A death doula, death midwife, or end-of-life guide, is a person who assists in the dying process much like a midwife or doula does with the birthing process. Often a community-based role, they provide emotional, spiritual, and physical support to families at an intensely personal and crucial time. The field has seen a significant rise in training organizations, which train deathcare professionals as well as interested individuals.

SOURCES

Dor-Ziderman, Y., et al. “Prediction-Based Neural Mechanisms for Shielding the Self from Existential Threat.” NeuroImage, Academic Press (8 Aug. 2019)

Holloway, A. & Kurniawan, S. (2010). Human-Centered Design method for Serious Games: A bridge Across Disciplines. Santa Cruz: University of California