What is my role as a product designer in a time when resources are running out? This is a question that many designers are struggling with as we have reached the point where we can no longer ignore the fact that we must be conscious of how we use our resources.

Sustainable products and materials have been dominating the design world in recent years. I too had reached the conclusion that the answer for me, as a designer, lay in discovering how to produce in a more efficient and non-polluting way.

But then I realised that materials and techniques are just one piece of the puzzle. In this article I argue that the core of sustainability lies in how we relate to the objects surrounding us.

Ikea

This insight started to sink in during my daily bike ride through the city on my way to work. Amsterdam city council collects bulky waste once a week, when people can put their discarded goods on the street for collection. Often, I noticed Ikea products amongst this waste − products that many people are familiar with, and may even be surrounded by while reading this article. Most of us, for example, are familiar with the ‘Lack’ table and ‘Billy’ bookcase.

Ikea was revolutionary when it created the principle of flatpack furniture that could be transported in flat packages and reassembled at home by the customer. This new concept kept the cost of shipping low, but at the expense of the quality of the furniture. ‘Pax’, for example is an Ikea wardrobe whose backboard is too large to ship in one package. So Ikea divided it into two parts that are connected with tape when assembling the wardrobe. Having a background as a carpenter, I can tell you that the backboard is the spine of any piece of furniture, because it gives it stability. Dividing it into two parts makes it unstable. As time passes, the tape dries out and loses its adhesive power. Obviously, tape can be replaced, but the remnants of old tape prevent the new tape from functioning perfectly. Eventually, it will come loose again. Furthermore, the backboard is assembled using nails rather than screws, which gradually loosen as the result of normal use. A few people will make the effort to fix this, but not everyone is able to do this or in possession of the necessary tools and knowledge.

As a result large numbers of the furnitures end up on the street, ready to be collected and burnt in the waste incinerator.

The High Cost of Cheap

I saw these products among the waste so often that I decided to take a photo every time I came across an Ikea product abandoned on the street. Before I took the picture, I looked for the trademark to make sure that I was right.

I collected these photos on an Instagram account named ‘highcostofcheap’. I chose this title because the number of pictures I took in addition to the amount of waste made me realise that the ‘actual price’ is much higher than the price tag suggests. By that I mean that resources are too valuable to use them for products that are not made to last.

The main material used for Ikea furniture is particle board, which cannot be recycled due to its plastic coating. What’s more, the circumstances under which these products are made are also questionable. Whole factories are dependent upon orders from Ikea, giving the latter the power to dictate the price and therefore, the circumstances of production.*

This is not an article against Ikea. Ikea is just one example of a company that built its business on the principle of low-cost and high-volume and by doing so it is representative and symbolic of the time we live in. A time in which a product’s quality is secondary to keeping the price of it low, as longevity does not seem to be what consumers are looking for in a product.

And so I realised that it would make no sense to design sustainable, durable products if people are not willing to keep them because they are longing for the next, new thing.

In his book, ‘Consumption’, Robert Bocock* writes: ‘Consumption is founded on a lack – a desire always for something not there. Modern/post modern consumers, therefore, will never be satisfied. The more they will desire to consume.’

And so I realised that it would make no sense to design sustainable, durable products if people are not willing to keep them because they are longing for the next, new thing.

Planned Obsolesence

In 1925 the Phoebus Cartel was set up by companies including Philips, Osram and General Electric to control the manufacturing and sales of light bulbs. The cartel members divided the market between themselves and agreed to produce light bulbs that lasted no longer than 1000 hours, even though it was possible to make light bulbs lasting 2500 hours. Their aim seems clear: the less time a product lasts the more often a new one needs to be purchased and the more profit is made. In 2007, Brother, Canon, HP and Epson were sued for doing the same thing. Their printers had integrated counters and stopped working after 2000 pages, even if nothing was broken. Error warnings also said that the ink cartridges were empty long before they had run out.

Our current economy is still built on planned obsolescence. We are encouraged to buy new clothes for each new season, or a new mobile phone every two years, even if the old one is not broken: as consumers we are trained to shop. This concept could only work if resources were endless: but they are not.

This story is not widely known but it needs to be told so that people – both designers and consumers − get the bigger picture of what we are part of. As designers we should be critical of what we design and for whom. Are our designs intended to last, or made for just one season? As consumers we should question low prices and keep in mind that someone or something has to pay the price if we do not pay it at the till.

The term ‘throwaway society’ entered our dictionary and is described by the Cambridge Dictionary as: a society in which things are thrown away as soon as they have been used.

Awareness

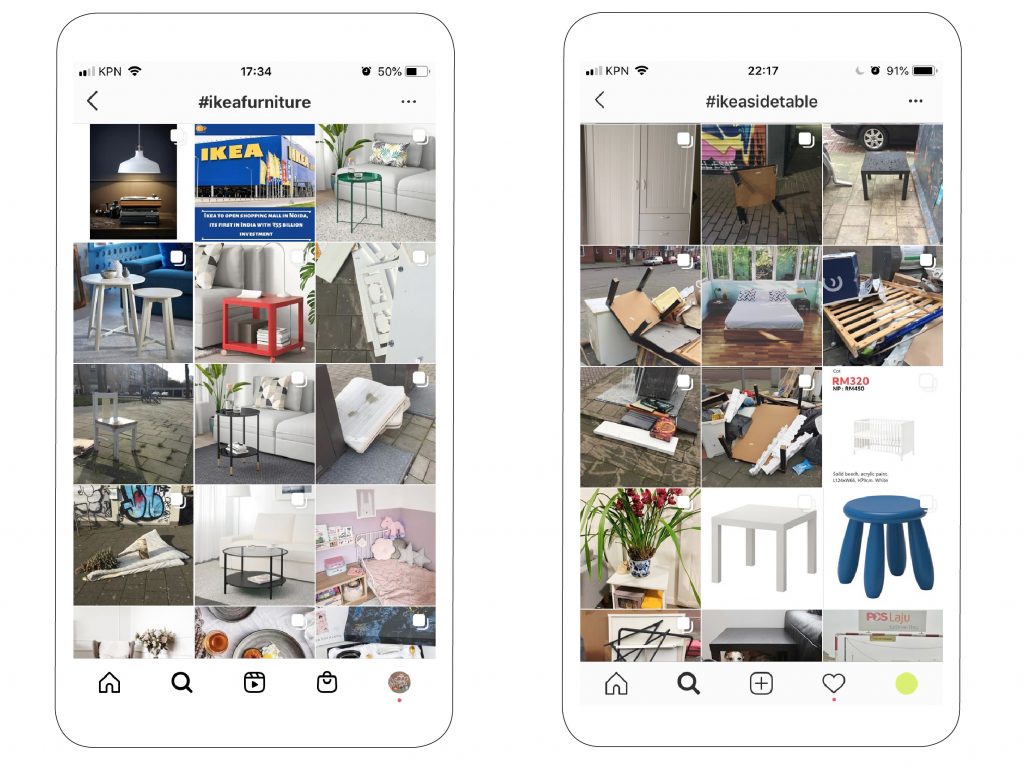

The pictures I took are a visualisation of our throwaway society. By posting them I wanted to confront people and raise awareness. Every time I posted a picture, I attached tags to attract followers. My reasoning was that the more followers I could get, the more people I would reach and the more consciousness I would raise.

By placing my picture next to an advertisement of Ikea, I wanted to show the correlation of cheap prices and throwing-away culture.

I discovered that you can attach 30 hashtags to each post and started searching for tags on other accounts with similar content so that I could reach people who are interested in waste prevention.

Friends and colleagues got to know about my new Instagram account and I had several conversations about it. Many people perceived my pictures as negative. When I asked why, one said: ‘How can waste be positive? It’s just not nice.’ I tried to discuss the behaviour that was causing these images. A few people argued that shops like Ikea make ‘design’ accessible for people without much money. I agreed on that.

But people also said that since looking at the Instagram account they had started to register the amount of bulky waste in the streets, whereas they had previously become inured to it. At least it seems as if the account has influenced some people.

Findings

Looking at the photographs I began wondering how much waste they actually depicted. I decided to find out the total weight of the waste for one month. In March 2020 I photographed 102 products. They ranged from sofas to baskets, but mainly they were wardrobes. I then looked up the names of the products I had come across on the Internet. Products that were no longer in production were a challenge, but old manuals or advertisements helped me to uncover their name or measurements.

I looked for similar items on Ikea’s website and used that weight in my calculations. I found out that many Ikea designs remain in their collection for many years. They are adapted to recent trends and usually became lighter over the years. The units of production are so high that every gram Ikea can save makes a huge difference to material and shipping costs.

The weight of the Ikea products I found during one month is 1546 kg. This amount converted into the amount of CO2 emissions during combustion is equal to 3077 kg CO2. A tree absorbs 20 kg CO2annually. To compensate for the products weighed that month, Ikea would have to plant 153 trees.

Is shopping at Ikea the new flying?

Lexicon

Planned Obsolescence

In economics and industrial design, planned obsolescence is a policy of planning or designing a product with an artificially limited useful life or a purposely frail design, so that it becomes obsolete after a certain pre-determined period of time upon which it decrementally functions or suddenly ceases to function, or might be perceived as unfashionable. The rationale behind this strategy is to generate

long-term sales volume by reducing the time between repeat purchases.

Throwaway Society

The throwaway society is a human society strongly influenced by consumerism. The term describes a critical view of overconsumption and excessive production of short-lived or disposable items.

Bronnen

Ellen Ruppel Shell, Cheap. The high cost of discount culture (Penguin Books 2010)

Robert Bocock, Consumption (Taylor & Francis Ltd 1993)

Thomas Rau, Material Matters (Bertram & de Leeuw Uitgevers BV 2016)

Ruth Mugge, Product Attachment (TU Delft 2007)

Volg Isabels werk en onderzoek hier:

isabelquiroga.com/

instagram

#highcostofcheap

Out of touch

As a result of this development, which started in 1925, we have become out of touch with the objects surrounding us. Products have become cheaper than ever and are exchanged so massivley and quickly that there is no time to build a relationship with them.

Of course, for the sake of honesty, I must say that there are people who treasure and preserve their furniture (including their Ikea furniture) and the ojects they are surrounded by. And as I already mentioned, low prices make things accessible for people with less money.

‘We need to find a new balance between our temporary need and the consequences of our decisions that far outlive us’

Thomas Rau in ‘Material Matters’

But I think my Instagram account clearly shows that for the sake of the following generations, we need to rethink our relationship with the objects surrounding us. We need to be more concious what we produce and in which quality. In his book ‘Material Matters’ Thomas Rau states: ‘We need to find a new balance between our temporary needs and the consequenses of our decisions that far outlive us.’

As designers we can play an active role to counteract the throwaway culture by encouraging a bond between object and consumer. Ruth Mugge* is a professor at TU Delft and found out in her research that the more we bond with an object, the more we take care of it and the longer we keep it.

In my thesis I will describe how designers can use their language of form, material and function, as tools to stimulate a durable relationship between user and object.

A long-lasting relationship stimulates sustainable behaviour and therefore plays an important role within the theme of sustainability.