Footwear is part of an unbroken proprioceptive loop which connects our brain, to the earth. Information we receive from our feet is being translated into signals. With minimal material, maximal proprioception can be experienced [1]. The choice of material for footwear is crucial for several reasons, as it directly impacts the comfort, durability, performance, and overall functionality of our footwear. Besides these factors, the choice of material will also have a huge impact on the proprioception that is experienced. The choice of material in this research is very well thought through; sustainability, animal welfare and ethical factors are always considered and seen as basic factors.

After having worked in the commercial footwear industry for many years, for companies such as ECCO, Bata and Loints of Holland, I started questioning why we make shoes such a complex product. The footwear industry generally uses materials sourced from all around the world, in which price plays the most important role. We look for the cheapest materials and labour, in order to sell shoes for an affordable price. This means that sometimes the material is purchased in one country, shipped to another country to stitch the upper and then sent to yet another country to add the sole to it. Moving all these components around the world requires a lot of transportation and CO2 emissions. It was during my time at Loints of Holland that I realised it is also possible to source materials within Europe. For my master’s program at Willem de Kooning Academy, I am researching if it would be possible to prioritize the health of our feet and environment by utilizing local resources instead.

After the Industrial Revolution, footwear became a bulk commodity and we lost our direct connection with our planet. We no longer know where the material comes from that our shoes are made out of. We do not even know who the person who made our shoes. With the introduction of the shoe last, shoes are no longer shaped for our unique feet but are moulded around a simplified shape of the average foot. However, according to the Future Footwear Foundation, traditional types of handmade, bespoke and eco-friendly footwear are considered ‘new-luxury’. [2]

The oldest shoe ever discovered dates back to around 5000 years ago. This shoe is made from leather and plant fibres and provides evidence of early efforts to create protective footwear. The leather is moulded around the shape of the foot and hay is inserted to add comfort and insulation. A very minimalistic product if you compare it to modern-day sneakers [3].

Current footwear does not only affect our proprioception and anatomy (think about the bulky, heavy-soled sneaker trend) but the production of it also damages our planet. We need to reconnect with our planet, both literally and metaphorically speaking. Can we use local resources to reconnect with our planet again?

In my years of studying footwear and its history, my eyes always fell on braided and woven shoes. Braiding and weaving have deep historical roots in various cultures across the globe, with evidence of their use in footwear found in ancient civilizations. Native Americans crafted their shoes using woven patterns, each design carrying cultural significance. The integration of braiding and weaving in historical shoemaking not only served functional purposes but also reflected the artistic and cultural values of the societies that employed these techniques. [4]

For this research project, I connect with local craftspeople and material innovators to explore new or alternative ways of shoe-making together with them. These people are generally very open-minded and inspire me to think outside the (shoe-)box.

Stepping into basketry

Current footwear does not only affect our proprioception and anatomy (think about the bulky, heavy-soled sneaker trend) but the production of it also damages our planet. We need to reconnect with our planet, both literally and metaphorically speaking. Can we use local resources to reconnect with our planet again?

In my years of studying footwear and its history, my eyes always fell on braided and woven shoes. Braiding and weaving have deep historical roots in various cultures across the globe, with evidence of their use in footwear found in ancient civilizations. Native Americans crafted their shoes using woven patterns, each design carrying cultural significance. The integration of braiding and weaving in historical shoemaking not only served functional purposes but also reflected the artistic and cultural values of the societies that employed these techniques. [4]

For this research project, I connect with local craftspeople and material innovators to explore new or alternative ways of shoe-making together with them. These people are generally very open-minded and inspire me to think outside the (shoe-)box.

Middle: sample of dried birch bark

Right: Dutch rush (biezen)

The materials that Mieke works with mostly are birch bark, willow bark and rush. Each material has its own characteristics:

Birch bark – a firm but flexible material that can be softened by temperature due to the tar inside the bark.

Willow bark – a hard and stiff material that can be softened by soaking it in water.

Rush – flexible, fragile material that can be softened by soaking it in water, can be woven very tight and firm.

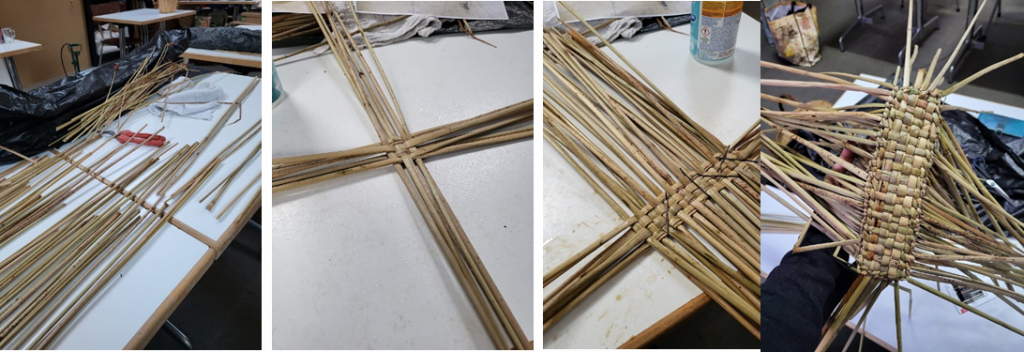

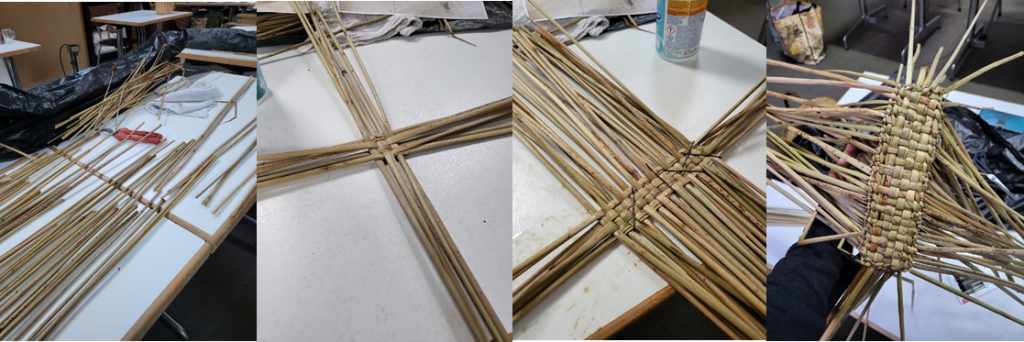

Because of its flexibility and ability to form a fine and firm structure, the first iteration is done using rush, coming from the Dutch wetlands. First, the rush needs to soak in water to become flexible and stronger. When it dries out, it will break in the weaving process. Once woven, braided or twined, the construction is strong and can dry out without breaking. The bottom of the shoe is constructed using the plaiting technique. Then the ends are twined around the rectangular bottom and find their way up around the shape of the foot.

This shoe is still very fragile, especially when walking on rough surfaces. For that reason, I also applied this technique and material on an already existing sole. I used a polyurethane (PU) sole which is designed for disassembly; meaning that it is easy to separate multiple materials and reuse or recycle them at their end of life. This sandal is only plaited, the advantage of this is that the ends can be pulled or loosened easily while they are still wet and therefore can be fully adjusted to an individual foot, even when it is made on a generic shoe last.

The sole is wearproof, but not locally made. The most well-known Dutch shoes are wooden clogs. They last a long time and are traditionally made of locally sourced willow and poplar wood [5]. I contacted Marijke Bruggink, who is a researcher and coordinator at Schoenenkwartier (the Dutch shoe museum) and Ambachtenlab (craft lab). She also collaborates with clog makers around the country and offered me a pair of wooden soles. The style of this sole is similar to the PU sole.

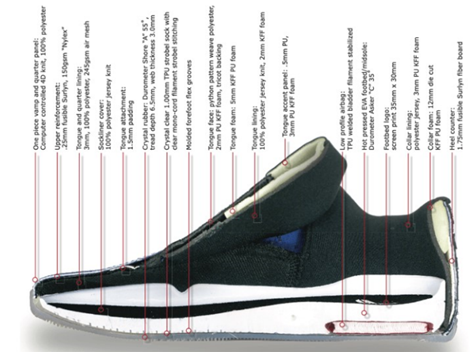

Now the sole is made from a local material too (this version I received came with a white PU outsole, but it can easily be made without it). However, in the first paragraph of this article, the importance of proprioception in relation to material was pointed out. The signals we can receive through this heavy wooden sole are limited and distorted (imagine stepping on a small stone; the sturdy wood blocks us from feeling it on the bottom of our feet). A vintage Nike shoe inspired me to create another type of sole, a moccasin type. A moccasin is an ancient type of shoe construction where the (leather) bottom of the shoe is stretched around the sides of the foot[6].

https://www.complex.com/sneakers/a/solecollector/the-history-of-nike-considered?utm_source=dynamic&utm_campaign=social_widget_share

https://sabukaru.online/articles/how-nike-jacquemus-is-reconsidering-old-principles

I wet moulded a piece of vegetable-tanned leather around the shape of my foot and started braiding the same way as with the first shoe. Because I had worked with rush a few times already, I wanted to try another material for the upper part. I found some natural fibre rope (jute) and tried using basketry techniques with it. The moccasin sole construction works well and is one to further explore. It can be made with locally tanned leather and the upper part can be braided with rush or locally sourced fibre material (wool, hair, flax etc.) making it a 100% local material shoe. With the use of a relatively thin leather sole at the bottom, giving it an almost barefoot experience, maximum proprioception is achieved.

References

[1] Catherine Willems, Feet and how to shoe them, in Els Roelandt, e.a. (ed.), Do you want your feet back (APE, 2018 #122), p.26-51

[2] Christine de Baan, Foreword-Future Footprint, in Els Roelandt, e.a. (ed.), Do you want your feet back (APE, 2018 #122), p.7-9

[3] Footwear design then and now, Aki Choklat, Footwear design (Laurence King, 2013), p 10-12

[4] Ben Bellorado, Leaving footprints in the ancient Southwest, p.20-31

[5] Europese klompen geschiedenis en verscheidenheid, Ted de Boer – Olij (South Sea International Press Ltd, 2002)

[6] Footwear design then and now, Aki Choklat, Shoe styles (Laurence King, 2013), p 47