Our world is overwhelmingly visual; the ability to see and interact with the environment is largely taken for granted. My research focusses on a world in which people read with their fingertips, not their eyes. By researching the boundaries of braille, imagery and tactility and exploring the expressive qualities of materials and techniques I aim to bridge the gap between the visual and the tactile.

DO NOT TOUCH!

How many times do children hear this order? No one would ever say: do not look, do not listen, but touching is different. Evidently a lot of people think you can do without.¹

Bruno Munari

Throughout history drawings have been used to tell stories, relay information and as a means of self-expression. But what if you can’t see? How do the blind use their sense of touch to ‘look at’ or read something? This article focusses on part of my design research concerned with the language of ‘tactile imagery’. For children and adults with a visual impairment, growing up and living in our westen ocular-centric culture, in which sight dominates all other senses, presents unique challenges. To illustrate the complexities involved in bridging the gap between the visual and the tactile, I will review two iterations: touch workshops for VI-teachers and a testing session in which young pupils review my designs. Both participants can be found in the context of special primary education.

My particular interest in tactile imagery stems from years of collaborating with special education for the development of tactile reading books which play a crucial role in helping children use their senses to construct mental images of the stories and concepts they explore through touch.

Theory of mind

Both the teachers and myself try to adapt to a different theory of mind by putting ourselves in the place of the visually impaired children. As a designer and as a parent to a blind daughter, I know all too well how challenging this can be.

‘Do fish have ears?’

… to cope with with haptic communication they (teachers and designers) must constantly navigate between two cultures and two different semiotic worlds: a sighted world … and a blind world which they try to imagine or experiment with …²

Dannyelle Valente

Tactile memory

During the touch workshops with VI-teachers (blindfolded) I first invited them to experience the communicative qualities of tangible materials using ‘tactile boards’ I had developed earlier this year. Subsequently I asked them to work in pairs. One had to describe an object whilst the other attempted to make a drawing of this object using a tactile drawing board. Once the blindfolds were removed many were surprised at how indistinct their tactile drawings were and how certain materials and objects looked very different from how they felt. ‘Tactile memory’ is a term often mentioned during conversations with VI-teachers as something which blind children find difficult and which requires a lot of training. In another workshop I asked a group of sighted (blindfolded) and non-sighted teachers to draw a tree. The sighted teachers focussed on the general shape whilst the blind teachers focussed very much on their personal experience with trees, the roots they fall over, the texture of the bark.

Design research method: touch and memory workshops

Children need to understand and to classify, to put order to what they learn. It is important to them that each thing and each fact has a name and that this information is given an order so that it can be recovered when needed. This is how communication skills are built up in language.¹

Bruno Munari

The visual and tactile: bridging many gaps

Whilst working on an Erasmus project to develop guidelines for tactile children’s books I realized that there is a huge gap between tactile collage books for very young children and the rather clinical tactile graphics books for older children; both are used in primary education as part of the curricula. One could say that there are many gaps: the visual and the tactile, the different theories of mind, the gaps in different kinds of tactile imagery, the gaps in knowledge and the gaps in accessibility and availability.

In an effort to bridge one or more of these gaps I am collaborating with Marianne van der Vinne (itinerant VI-teacher, didactic researcher at Visio Education), on a new concept which I have proposed and which has been accepted. We are developing a tactile reading book to help children with a visual disability (6–8 years old) make the transition between different kinds of tactile imagery. The idea is that the storyline will run hand in hand with the sequential development of meaningful tactile illustrations: from solid material shapes (collage) to more abstract representations (tactile graphics) using printed outlined shapes, textures and braille. When finished the book will be distributed to all the VI-teachers to use with their young pupils as a new teaching aid.

To be effective, a tactile illustration should provide the reader with a tactile experience that, along with the book’s words, triggers a connection with the child’s own experience of the object in everyday life. ³

Carinna Parraman

Stimulating curiosity and imagination

In order for Marianne to craft the story and for me to develop meaningful images, we thought it a good idea to look more closely at the children’s understanding of what a drawing is. We both have our own expert experience as well as knowledge of relevant scientific studies but sense a certain mismatch between the theory, the adapted school books (designed for sighted children) and what actually ‘works’ in the classroom. To kick-start the design research I created a series of tactile images, based on an earlier book we had developed together, and tested these with the young pupils. We were very fortunate to be able to conduct the testing with 7 young children with various degrees of vision (dis)abilities; a heterogeneous group but all learning to read braille.

Design research method: collaborating and testing sessions

Liberating the analogical imagination

Jan Ŝvankmajer, the Czech filmmaker and artist connected to the surrealist movement ‘uses tactility to dissolve the descriptive registering of the world that sight is so often the hallmark of, in an attempt to liberate the analogical imagination of touch’⁴. Furthermore, according to Svankmajer, ‘The senses are not discrete, but interrelated. We are all synesthetes’⁴. To help the children make a connection between a real fish and a drawing of a fish I included a real one in the testing session. I think Marianne was just as surprised as the children, two of whom (both partially sighted) were too squeamish to touch the fish. However the other children, some tentatively, others more freely, were all curious enough to explore the fish with their fingers. Perhaps they had never felt a fish before; in our own enthusiasm we forgot to ask. Later, when I was reviewing the hours of film clips I could actually smell the fish and imagine it’s slimy body.

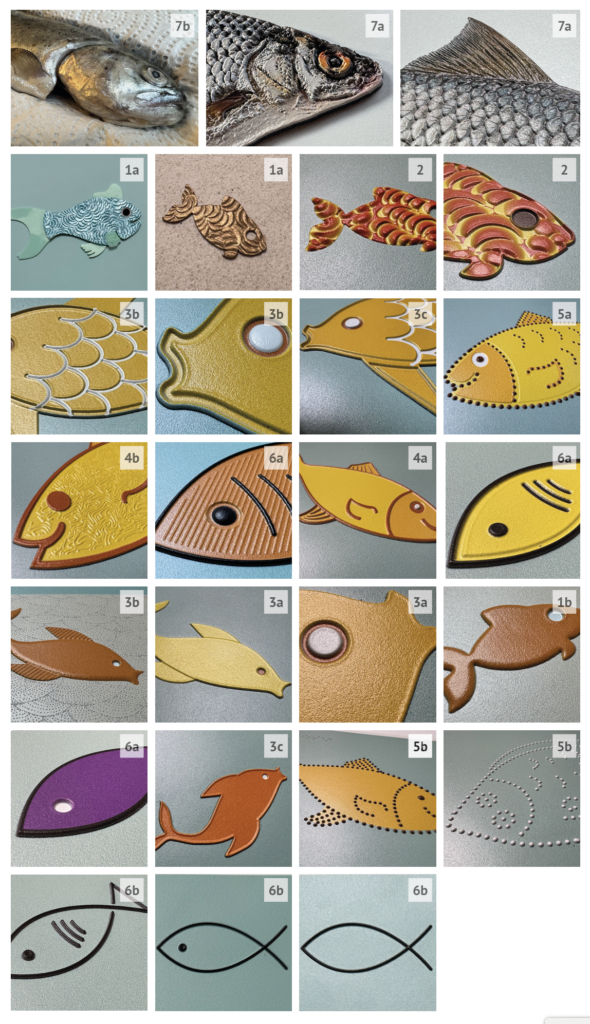

Designing tactile imagery for print

Simply adding raised lines to an illustration or drawing for the sighted can result in a jumble of shapes and lines which make no sense to someone whose world is not visible. What may seem clear to the eye can appear very cluttered when reading by touch. One of the most important factors when designing any kind of tactile imagery is to select the most essential elements and make these detectable to touch. Unlike collage books in which the unique properties of materials can provide very direct tactile clues, printed imagery relies on the arrangement of shapes, lines, patterns and functional spaces to give enough haptic feedback for a child to build a mental image.

From an early age, sighted children are exposed to a rich visual language of text and all kinds of images ranging from drawings with perspective, moving images, to cartoons, icons, symbols and so on. Would the young children, in particular the congenitally blind children, testing the tactile images recognize all the fish, even the very simple but abstract representations?

The actual diversity in the representations of fish wasn’t as problematic as I might have expected. Perhaps this was partly due to the fact that the testing was carefully carried out in a specific order and with ‘hand over hand guidance’ from Marianne who instructed the children and asked the design research questions. Involving the children in the design process at this early stage of writing and designing has provided very worthwhile feedback. It was obvious that some children were using either their visual memory or residual vision and for this reason I was particularly interested in observing the blind children. On the whole the children were very clear with their comments about which renderings and combinations were easy or difficult to understand and why.

Many pictorial illusions that artists use, such as perspective or vanishing points, and placement of objects to suggest depth are pictorial concepts that have been learnt and understood.³

Carinna Parraman

Elevated printing (2.5D)

To print the tactile sketches for the testing session I decided to explore the tangible properties of elevated printing, also know as 2.5D, with new software allowing a range of up to 2 mm relief. The inks used are synthetic and feel very solid, even hard. During the testing the children described the feel of the ink as ‘like plastic but very clear to touch’. In fact several children either ticked on flatter surfaces or ran their nails over textures creating sounds which made them laugh. This technique prints good braille and is very flexible in modeling illustrations. For the fish I used a wide range of renderings to see which would create the most tactile contrast, convey the most information and be pleasurable to touch.

References

¹ Bruno Munari, The Tactile Workshops (Mantova: Maurizio Corraini, 1985), p. 3, pp. 6-24.

² B. Darras & D. Valente, ‘Tactile Images: Semiotic Reflections on Tactile Images for the Blind’, Terra Haptica, the Haptic International Journal, No. 1 (Talant: Les Doigts Qui Rêvent, 2010), p. 2, pp. 1-15.

³ Carinna Parraman Maria V. Ortiz Segovia, 2.5D Printing: Bridging the Gap Between 2D and 3D Applications (West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2018), pp. 145-151.

⁴ K. Noheden, ‘The imagination of touch: surrealist tactility in the films of Jan Ŝvankmajer’, Journal of Aesthetic & Culture, Vol 5 (Stockholm University, 2013). p. 3 and 4 resp. and pp. 1-12.

⁵ Chancey Fleet, ‘Humans and Technology: How tactile graphics can help end image poverty’, MIT Technology Review, the Accessibility Issue, July/August 2023, p. 5.

Further sources

F.T. Marinetti, ‘The Manifesto of Tactilism’, Paris 1921.

Jan Ŝvankmajer, Touching and Imagining: An Introduction to Tactile Art (London: I.B.Taurus & Co, 2014).

Susanna Millar, Reading by Touch (London: Routledge, 1997).

John M. Kennedy, Drawing & the Blind: Pictures to Touch (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993).

Ans Withagen, Tactual Functioning of Blind Children, (Ede: GVO, 2013).

E.S. Axel & N.S.Levent, Art Beyond Sight: a resource Guide to Art, Creativity and Visual Impairment (New York: AEB & AFB Press, 2003).

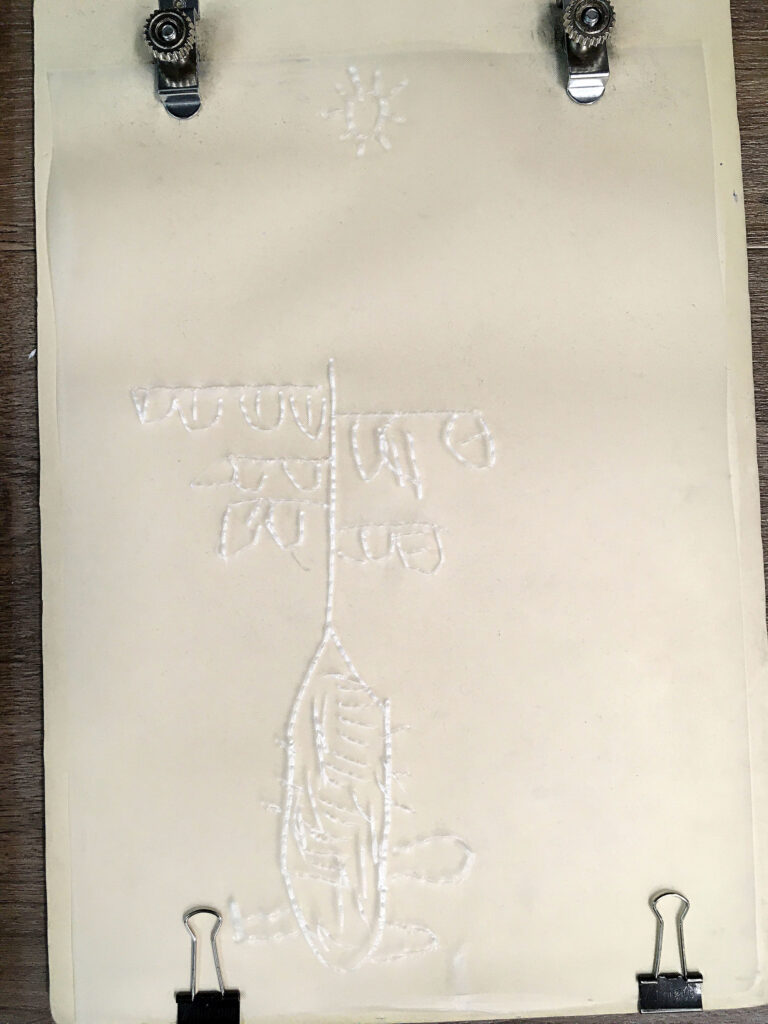

Drawing to understand drawings

In addition to the book there will be extra exercises and learning materials such as 3D models and Swell drawings. Furthermore I think it would be very beneficial if the children made their own drawings of fish. For several years I have worked with my own daughter, teaching her the basics of tactile drawing. This experience together with my participation in the development of a tactile drawing method for education which will be launched later this year, have lead me to believe that teaching blind children to draw themselves can help the process of understanding other drawings.

Discovering tactile imagery and learning to draw your own will undoubtedly encourage creativity, personal expression and imagination. In short enrich language and communication skills, build confidence and independence thus helping to narrow the gap between the visual and the tactile.

Tactile drawings can unlock strengths and possibilities in spatial learning and creation that blind and low-vision patrons might never have discovered.5

Chancey Fleet

Keywords

Tactility, tactile imagery, tactile aesthetics, blind, braille

Glossary

Tactile collage books: books fabricated using mixed media, for instance a combination of (raised) print techniques and all kinds of tangible materials; tactile books for toddlers are often entirely made from fabric.

Tactile graphics: term used specifically for raised line drawings, sometimes in combination with patterns or textures for text books, art illustrations, maps, diagrammes, charts and graphs. These are produced by Printing Houses on Swell paper or by using vacuum forming on plastic.

The tactile drawing board: tool for non visual self expression. I have developed a low-cost, self-made board.

Swell form tactile graphics: special microcapsule paper, printed with carbon ink is fed through a heating machine; a chemical reaction causes the black lines to puff up and form raised lines. This is a relatively simple, fast and low cost method of reproducing tactile graphics and braille.

2.5D printing: layers of white ink are applied to build up the textured height (0-2 mm in the case of the tactile drawings which I design), followed by the top coloured layer and if required a final UV coating for extra protection.