Belonging is one of our essential emotional needs. what happens when we find ourselves in a new home and that feeling is missing?

In my design research i explore how defining belonging together with participants affects their emotional attachment. Through different design research methods we discover how to approach this feeling and what tools are necessary to ‘reclaim’ it. In this blog post i elaborate on the two iterations in which defining belonging has a central role.

Cultural Belonging

The discourse on belonging and notions of home has the peculiar effect of being relatable to many. Nearly everyone can understand either the feeling of belonging or the absence of it. Belonging is one of our essential needs, and though it can be applied to a plethora of different contexts such as psychology, sociology, politics etc., in my design research I approach it as cultural belonging.

This design research started from a personal longing. Being from two cultures, I have always questioned where and how to belong. In my artistic practice I discovered the many different connections people have to this feeling, as well as the amount of people experiencing the absence of belonging. And yet, this feeling is difficult for people to put in words. Which is why this quote from psychologists Jeroen Knipscheer and Rolf Kleber has such a strong metaphoric connotation:

Cultuur is als water voor de vissen: je bent erdoor omgeven en zonder kun je niet bestaan – maar je bent je er nauwelijks bewust van.

Knipscheer & kleber, p 12

Culture is like water for fish: you are surrounded by it and you cannot exist without it – but you are hardly aware of it.

Culture is such an intrinsic thing, we learn the cultural cues and signifiers at a period of life when we don’t question new information as we would in an adult age. Just like belonging, our relationship with culture is more a feeling, a connection we feel but fail to explain when asked about it too explicitly. And so we only discover what has been integrated in our being when we find ourself in a new cultural context.

Zoals een vis pas op de kar van de visboer tot de ontdekking komt dat zij een waterdier is, zo beseft de mens pas in contact met mensen uit andere samenlevingen, met andere gewoonten en met andere zeden, de betrekkelijkheid en daarmee ook de culturele context van zijn eigen gedrag.

Knipscheer & Kleber, p 12

Just as a fish only discovers it is an aquatic animal on the cart of a fishmonger, so does a person only realise his/her own relativity and with it the cultural context of his/her behaviour, when in contact with people from a different society, with different habits and morals.

Belonging in a new cultural context

In my design research I look into the feeling of cultural belonging for people who have transitioned into a new cultural context. This change does not always come without its tremors: People engaged in transnational practices might experience an uneasiness, a sense of fragmentation, tension and even pain*. (Al-Ali & Koser) Subsequently, in my first design research method I asked my participants to define what they missed most from their previous cultural context in order to gain some information on the different definitions of belonging. I asked them to show this by means of a (temporal) tattoo. This way the definition and meaning which they gave to the colours and shapes, became of personal value to the participants, as they place it onto their body.

Design Research Method: Homesick Tattoos

After sending out the design probe, I expected to get results based mainly on the amount a particular colour was used. However, by asking extra questions so the participants could go in depth about their choices, I discovered the effect defining belonging had on them. While for me belonging is an everyday theme in my life, others don’t always have the right words or tools to help them discover what it is they are feeling, even though they experience the absence or the longing.

LEXICON

Cultural Belonging

Belonging is a feeling of comfort and security based on “the perception that one is an integral part of a community, place, organisation, or institution. (Asher & Weeks)

When alright, belonging to a culture can offer a sense of comfort and security. In this case culture alludes to habits, morals, traditions etc. These cultural markers help us to navigate through life and when we recognise them in our context, it makes us feel comfortable and safe. When we are familiar with the cultural markers of our surroundings, and these are in correlation with our (cultural) identity, we can form an emotional attachment to said context. As defined by a participant, cultural belonging includes knowing the social cues and expectations, and to her this knowledge offers a sense of freedom to exist and to be herself.

New Cultural Context

A new cultural context is any place, ranging from villages to continents, which is different from our previous cultural context, and in which we can speak of the existence of another culture. It also means that the transition undergone to reach the new cultural context is recent, otherwise we would not consider it new anymore. However the newness is not only counted in time, but in the adjustment of the person who has experienced a cultural change. For one person adjusting to a new culture can be a quick process, while for another it might take years.

Redefining Home

Redefining home is an act of taking definitions of what we consider to be and feel like home and applying them to a new context. In this process definitions get a new meaning and place in our emotions. It is part of an adaptive process to feelings of dislocation (Butcher) and includes reaffirming existing boundaries and re-defining new ones. When redefining we become aware of our own cultural identity and try to find the right adjustment for it in a cultural context which, in the process of dislocation, is different than our previous context. This is valuable to our sense of belonging as, according to Fenneke Wekker, when we understand and recognise these feelings, we are able to understand in which social interactions and relationships such feelings are likely to occur – or not.

Looking at the results, for most participants, making the tattoo made them realise what was most important to them. But when looking deeper into it one participant discovered how the unpredictability of his transient lifestyle forms his relationship to belonging, and found what he feels most connected to are the people and not the place or language, as he has multiple of both. Another participant spoke of the role connection has in her relationship with belonging, both the actual connection to people as the means to connect, such as music and language. In their reflections they wrote that they were grateful to realise and put in words (and shapes) what home meant to them.

It showed me once again that home is not a place but the people.

It made me realise that in the end, the most important thing for me are the people around me.

I’m glad I was able to find my own definition for what I missed specifically.

Designing our own sense of belonging

Thus, while in my design research I focused on What defines belonging? I now included the notion that belonging can be something one decides to do, and that the power to do so lies both in taking action as in being able to define the ‘location’ of this feeling. Here it needs to be said that there is always a relationality to be taken in consideration when ‘deciding to belong’. Sometimes constructs of identification are placed upon us and we cannot escape them. This is however part of a more political approach to study the sense of belonging and something which I will not get into in this article.

We are the designers of our own sense of belonging.

Said by sociologist Maggi Leung during the (Making) Sense of Belonging-program at Pakhuis de Zwijger in June 2021, this quote and the discovery from my first iteration led to the main method I am developing for this design research, to define and capture the sense of belonging. According to political sociologist Fenneke Wekker once we are able to recognise feelings of home, we will also be able to understand better in which social interactions and relationships such feelings are likely to occur – or not. And so in the next iteration I designed the material in that way that the participant would have the right tools to discover their own personal definition of belonging and to capture this for future reference in life.

Design Research Method: Memorising Belonging

The design research method, called Memorising Belonging, is the one where I first started to actively implement the approach to define and capture the sense of belonging. Inspired by a colleagues use of memories as a tool I developed a re-framing method whit which I could talk to a participant about how they remember feeling a sense of belonging. In a video interview we talked about each others memories, starting from belonging to friends and proceeding to how we remember the feeling of belonging to our cultural context.

In design research the influence of language and of design have an important role, they are tools which guide the research. In this method I re-framed the question to first connect to something recognisable.

When do you feel like you belong with your friends?

After discussing the answers to this question, it was easier both for the participants and myself to grasp how we experienced belonging in our culture. In my design research the interaction between me as a researcher and my participants goes two ways. As they help me discover answers to my questions, I make sure that the revelations which come out of the methods are given back to them in a form which is of value to their sense of belonging. In the case of the video interview, I took a screenshot at the moment they thought or talked about their memory of belonging and made it into a ‘wallet photo’ with their quote on the back, to be used as a reminder.

At first, when discussing the memory, it would sound as ‘speaking our secret language’, ‘eating with my family, where everyone speaks at the same time’ or ‘wearing orange sunglasses and t-shirt on Kingsday in Italy’.

As we continued talking about these memories, it became clear for instance that the secret language is a way to share similar identities for this participant and other people who have a similar background. It was a ‘new’ language, a combination of two languages, which could only be understood by those who shared both cultural backgrounds.

For another participant, eating with her family meant that she could be herself without overthinking it, because she knew the social cues and expectations. This is something which can be found in theory too, according to Knipscheer & Kleber culture provides security. Cultural habits and customs are ‘signifiers’. They prevent a person from having to decide and improvise every moment.” Or, as social and cultural geographer Melissa Butcher said ho home can be seen as a necessary stabilising weight.

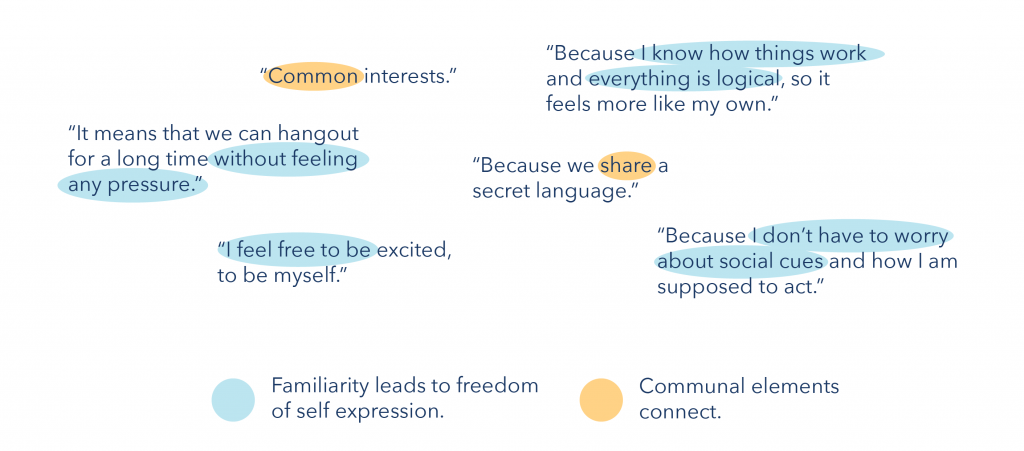

Defining feelings of home is part of an adaptive process and as such has an important role of finding belonging in a new cultural context. It creates awareness of the signifiers and emotions we have connecting to home. In deeper conversations about the memories with my participants, we came to the conclusion that the feeling of belonging had something to with familiarity and connection. The collection of ‘definitions’, as seen in the image above, shows an array of similar experiences of belonging. Knowing how things work, what the social cues are resolved in an absence of pressure and freedom of self-expression, freedom to be excited and oneself. While on the other side the communal elements made for connection and bonding.

When these definitions are captured, as they are on the photographs (these I gave back to the participants as reciprocal action, and they form a captured definition for them to use to remember the feeling they described), they are translated in a type of agency and form a strategy of adaptation, as they can now be taken into the new cultural context of the participant and applied to it to create a new home.

To conclude, in redefining home in a new cultural context we apply what has become visible through our own definitions and use this to re-create our sense of belonging.

REFERENCES

N. Al-Ali & K. Koser, Transnationalism, International Migration and Home, in N. Al-Ali and K. Koser ed., New Approaches to Migration? Transnational Communities and the Transformation of Home (Routledge, 2002) – p.7-8

Stephen R. Asher & Molly Stroud Weeks, Loneliness and Belongingness in the College Years, in Robert J. Coplan & Julie C. Bowker ed., The Handbook of Solitude (John Wiley & Sons, 2013) – p.287

Melissa Butcher, Managing Cultural Change: Reclaiming Synchronicity in a Mobile World (Routledge, 2011) – p.66-67

Jeroen Knipscheer & Rolf Kleber, Psychologie en de Multiculturele Samenleving (Boom, 2017) – p.12

Fenneke E. A. Wekker, Building Belonging: Affecting Feelings of Home through Community Building Interventions (Amsterdam University Press, 2020) – p.40