We all know what to do to move from a linear to a circular supply chain. It seems so simple: produce and consume less, choose renewable and recyclable materials, use responsible production methods, design for longevity and biological or technical cycles. So why is most of the textile industry still operating by the old linear model? Why is it so hard to produce sustainable textile products? This is the question I asked in the project Going Circular Going Cellulose or GC2.

The GC2 project is a collaborative research between Saxion University of Applied Science and ArtEZ center of expertise FutureMakers with several Dutch textile producers and designers, around creating circularity in the textile supply chain. I was interested in joining the project because it comprised the entire production chain. Designers were involved early on in the process of product development, which provided a lot of freedom and a broad scope to do research. The limitations were mainly material (cellulose-based fiber*), and production technique (weaving).

A simple tea towel

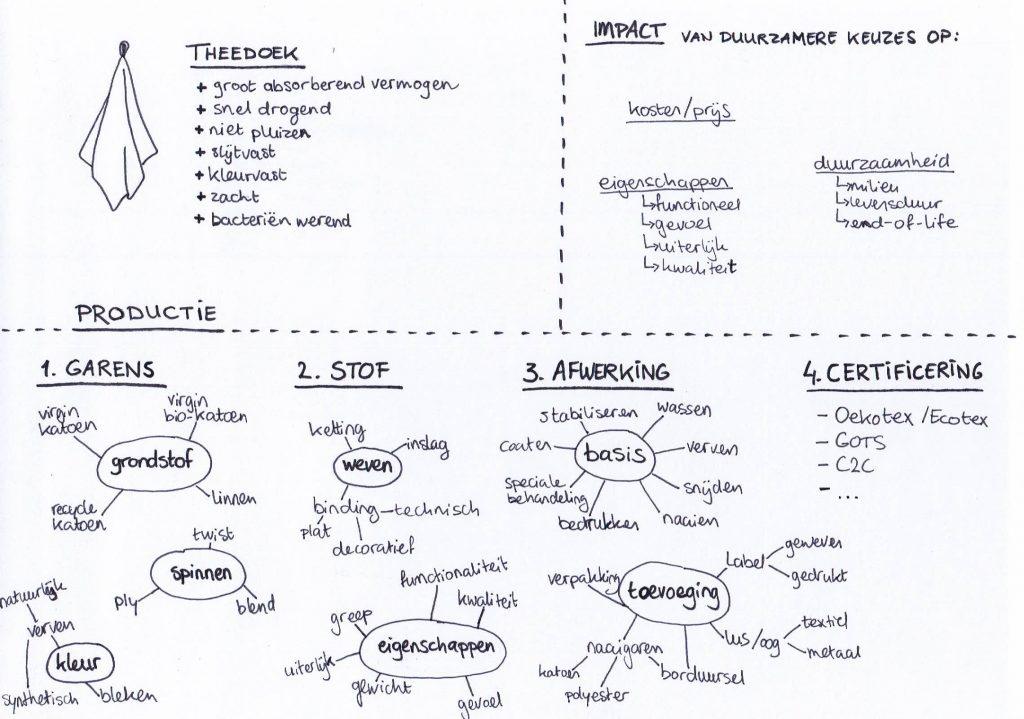

In the early stages of the project there were many company visits and discussions with the different stakeholders involved, each struggling in their own way with definitions of sustainability and circularity and how to make changes in a globalised textile supply chain. There was so much there to unpack, that to prevent getting overwhelmed by information I decided to choose the simplest textile product I could think of as an entry point to the textile production process: a tea towel. I deliberately chose this everyday textile as the lens through which to view the larger system and unravel its complexity because it’s so (apparently) basic, and more functional than fashionable.

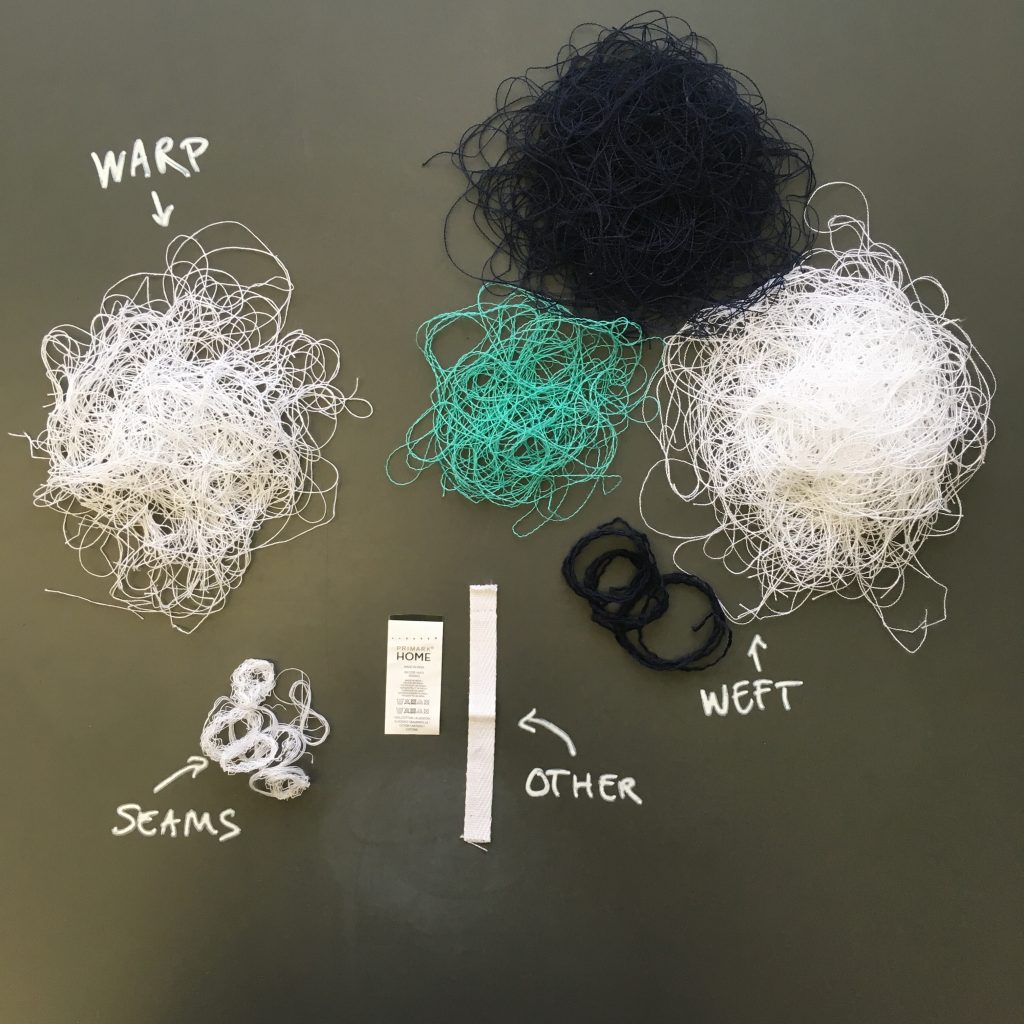

I bought a cheap set of cotton tea towels (a four pack for €5,- at Primark), as a benchmark example of textiles from a linear system. They were produced to compete on price and not much else. Had they been produced according to circular design principles, they would undoubtedly be different. Choosing more sustainable materials and production processes could alter the price, the performance and the look of the product. Literally picking one of the tea towels apart, helped me to break down the production process into detail. I could then sketch an image of this complex and interlinked system, and explore how it could be different.

Unravelling textile production

Separating the warp and weft*, the label, the ribbon and sewing threads left me with piles of different yarns: some thicker and others thinner, some bleached and others dyed. By mapping these different components and production steps, I created an overview of design decisions to be made in the production process. From the choice of warp and weft yarns, to how to weave and how to finish the fabric. All the options added up to a huge variety of possible fabrics, all with different characteristics and qualities.

To really map out all available options would be nearly impossible, but it was possible to identify the key steps in the production process where better choices toward a more sustainable outcome could be made. But here’s the cru: do these choices really result in sustainable products? Can a long lasting, responsibly produced tea towel from recyclable materials be sustainable if it doesn’t dry your dishes very well? What if it’s ugly and expensive? Circularity does not equal sustainability and sustainability has social and economical facets as well as environmental ones that need to be measured and compared.

With the design and production process visualised like this, it’s suddenly obvious why it’s so hard to produce sustainable textile products: there’s tradeoffs in every step of the way from fiber to product. Things like the use phase and end of life scenario need to be considered all the way from the beginning. If you try to focus on a single objective, like creating the product with the lowest environmental impact, that means compromising elsewhere on aspects like affordability and performance. Each choice may impact every other choice in intended and unintended ways. Choosing a sustainable recycled yarn, may for instance rule out certain production options and force you down a less sustainable path later on. A product that’s practically perfect in every way appears unattainable.

Sharing the challenge

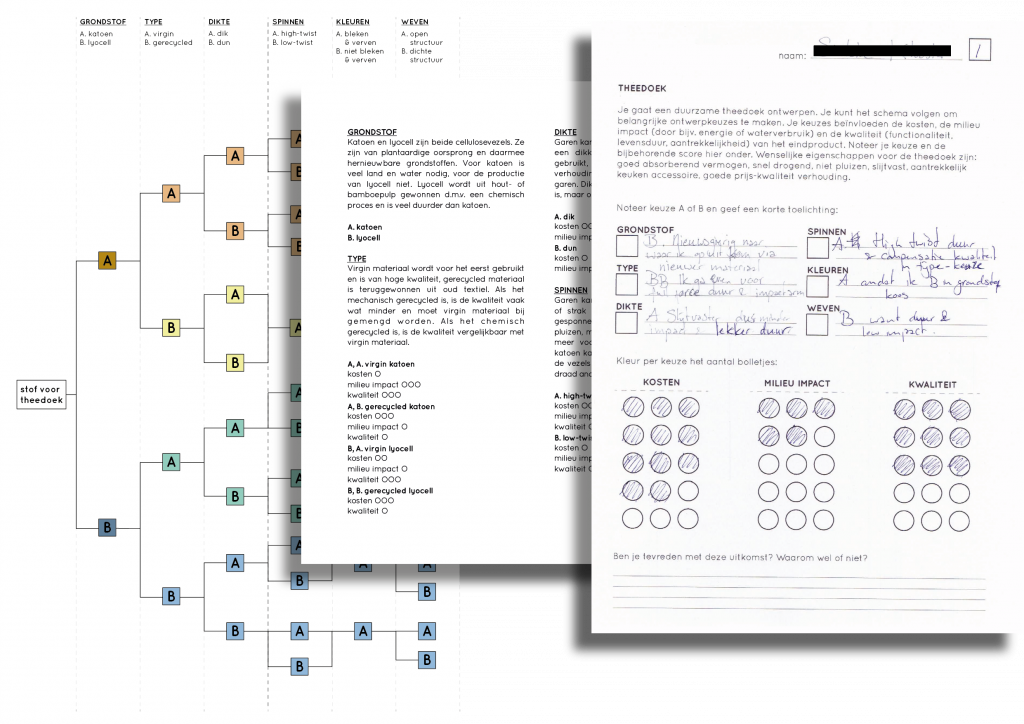

To see how other designers would respond to the challenge of creating a sustainable product while having this overview of connected options, I created an exercise in which they would also design a tea towel.

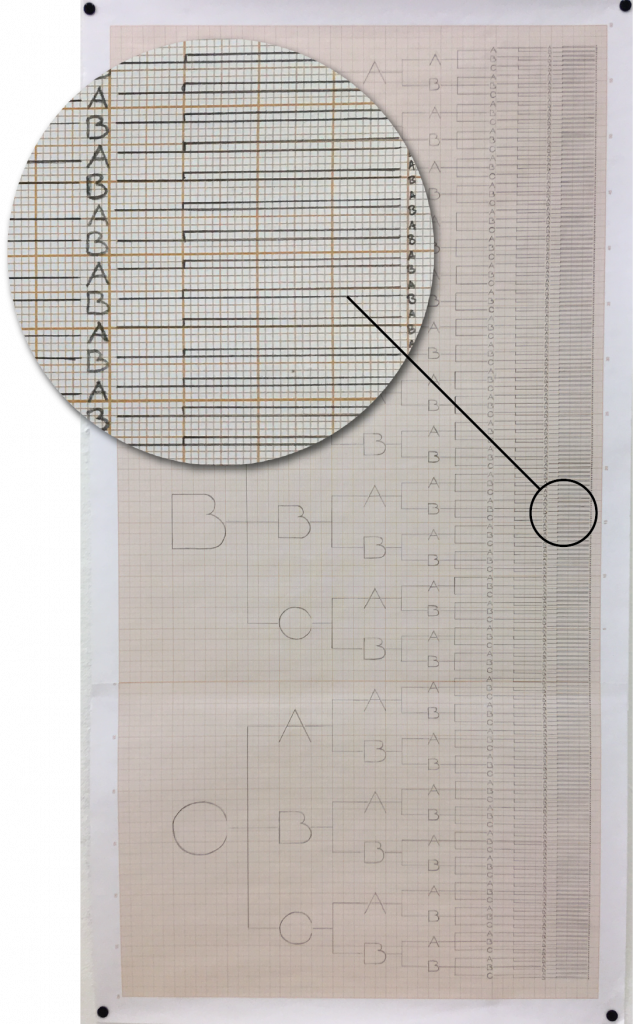

I made a simplified version of the production process diagram along with a document that explained each step and how each option influenced the end product. Each option had a corresponding number of points in three categories: cost, environmental impact and quality. I provided a form on which participating designers could score their concept in each category and describe their reasons for picking specific options over others.

I asked the designers to come up with what they thought would be the most sustainable, cheap or best quality tea towel and record their choices and reasoning.

All found it much harder than they anticipated to come up with something that achieved their intended goal. It was eye opening for them to see how much their choices affected one another and how the score added up in the final product. The highest quality outcome turned out to be extremely expensive, the most affordable outcome was terribly unsustainable and the most sustainable outcome lacked in quality.

Assumptions the participating designers made about what a “good” decision was, were immediately challenged when they saw how it affected the options they were left within the following steps, but it also allowed them to work backward. Going through this exercise individually, while sitting at a table together led to valuable discussions. It was striking how much they had to compromise, and they all left with a much better understanding of the challenges in designing truly sustainable textile products.

Lexicon

impact

The level of change an action causes is its impact. It can only ever be partly measured because impact can both be intended and come as a side effect. Lately “impact” has become a bit of a buzz word used in start up culture to imply a lot but mean very little. The impact I’m talking about specifically is the influence design can have on the way we view our systems of production and consumption. Partly through commercial product design, but also by critical and speculative design approaches.

Responsibility

Responsibility can be given or taken, but unlike accountability it’s always shared. Feeling responsible can be uncomfortable because the boundaries of responsibility are fuzzy. However, responsibility is interconnected with the freedom to make decisions. That is exactly why designers should explore theirs. Design choices affect entire supply chains, so should be made with mindful optimism that can be found in an awareness of responsibility.

Value

Value is a very rich term. Financial profit is only one meaning of this multi-faceted word. Creating value for me comes from closely observing something and finding something new in it, something useful. This can be value to the environment (something is nurturing), psychological value (something is satisfying), educational value (something generates an insight) and so on. To measure prosperity, as many facets of value as possible should be considered.

In practice

Working out this diagram of possibilities on paper was already quite insightful and proved valuable for designers wanting to create sustainable products. Though this is not intended as a life cycle analysis (LCA), it could also be a useful tool for textile producers to explore sustainable production options. LCA’s are made using very specific information about the production process (such as how much distance the product travels from raw material to end product and by which means) whereas this method compares every option relative to the other options considered in that step, and can be made before the specific information needed for an LCA is available.

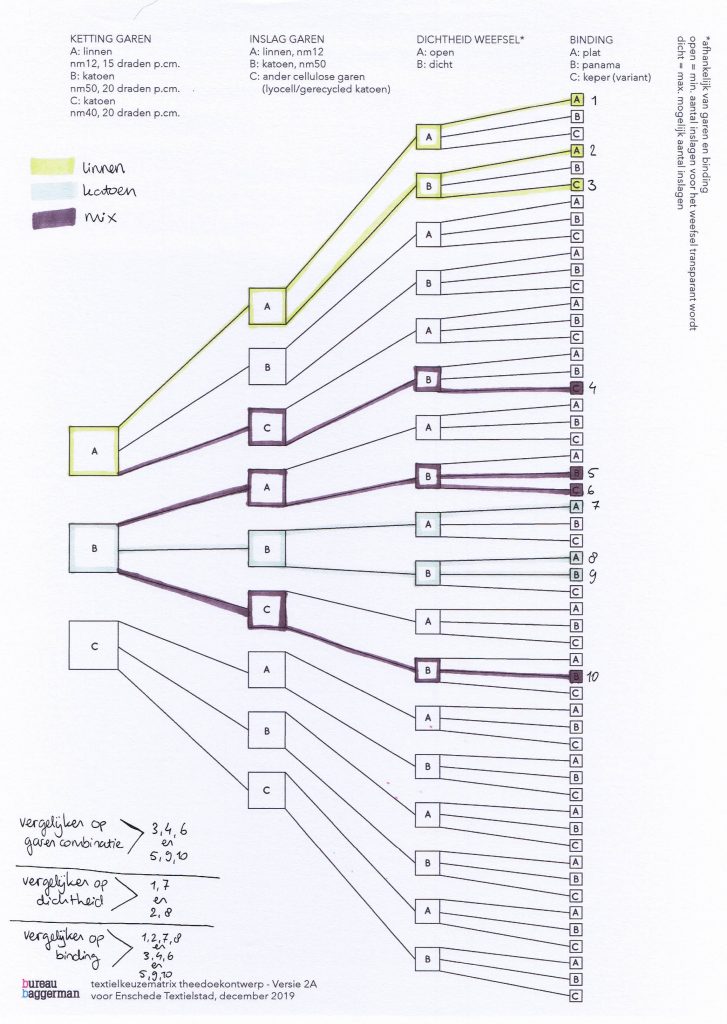

However it’s hard to imagine what the tangible end result might be like. The designers I tested the model with earlier confirmed this. To really visualise the story of the complexity in textile production, I found it important to also produce a range of different combinations resulting from this abstract diagram. To do that, and also test the relevance of this method for a textile producer, I collaborated with Enschede Textielstad*.

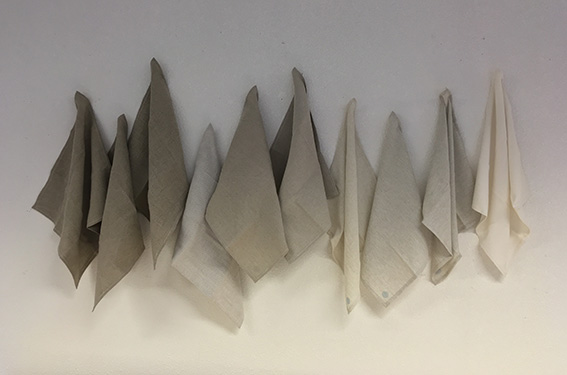

The diagram was adjusted to fit the production process within the company and led to a model consisting of four production steps and two or three options in every step. This amounted to 54 possible combinations, and using the diagram it was very easy to eliminate certain combinations, and select a range of ten fabrics that would cover the spectrum of possibilities and be comparable.

Immediate feedback from Enschede Textielstad was how useful such an overview would be to explain their production process to clients, who often don’t have the kind of knowledge that allows them to understand the possibilities and complexities of textiles* The ten selected samples were woven and finished, resulting in ten tea towels that could be compared on environmental impact, cost, functional performance, but also look and feel. These ten tea towels make it even more apparent that something that is very sustainable in theory, might not be so sustainable in reality. For instance one of the samples is so light and thin it’s clearly unsuitable for the wear and tear of use in the kitchen.

In conclusion

I set out to explore the process of creating a sustainable textile product by deconstructing and analysing an unsustainable textile product and re-engineering and designing it with the aim for it to become as sustainable as currently possible. In the process different interpretations of sustainability were shown through diagrams and prototypes, which illustrated how more sustainable choices affected the final product.

That there is much more to textile than just a warp and a weft crossing is no surprise, but being confronted with this through the diagrams and the tea towel samples, is different from just conceptually knowing that it’s complex: it’s experiencing how complex. This research helps understand why it’s so challenging to make a truly sustainable and/or circular textile, but also uncovers opportunities for change and suggests where interventions are most needed and/or likely to have a big impact.

The range of prototypes serve as a tangible communication tool, helping designers, and producers in the textile industry to compare how effective and feasible different ways to make a textile more sustainable currently are, and subsequently make better choices.

REFERENCES

Cellulose is the main component forming the cell walls of plants and can be used in textiles either as natural fiber (cotton, linnen, hemp, etc.) or man made fiber (viscose, rayon, lyocell, etc.). Cellulose is a renewable resource, although that does not mean using cellulose is always environmentally friendly. Cellulosic textiles can be reclaimed to create (partly) regenerated yarns using mechanical or chemical processes.

The warp is the set of vertical threads on the weaving loom, they need to be strong to sustain the tension of the loom.

The weft are the horizontal threads passed between the warp, they don’t need to be as strong. The way the weft crosses the warp is called binding. The combination of different warp and weft yarns, and the kind of binding used defines in large part the look and feel as well as the performance of the final fabric.

Enschede Textielstad is a small Dutch weaving company that locally produces sustainable textiles for fashion and interior.

The possibilities and complexities of textiles are not always understood. Clients will for instance ask for ‘blue fabric’, which you could compare to simply ordering ‘meat’ at a restaurant. On the other side there’s clients who think anything is possible, which is like expecting you can order sushi at an Italian restaurant because there’s dishes with rice and fish on the menu.

See recent projects and publications on circularity in textiles:

Trash2Cash project

Circular Textiles Ready to Market

Closing the Loop – Design Guideline for Recycling